|

| What's the difference who I am or if I am? |

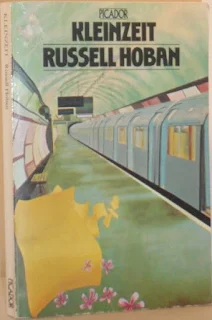

In an odd way, this short novel feels like an episode inside the head of Leonard Rossiter. A healthy man feels a mystery pain, checks himself into hospital and quickly unravels. But he also looks for a way out of a stultifying career, a lifestyle and emotional state where he can't remember his parents, ex-wife and children, unless he can physically visit their house / graves. He embarks on a literary career, selling poems on the platforms of the underground, writing a novel freehand on yellow foolscap paper. He explores a profound connection with a beautiful but flawed woman he barely knows. And he suffers the medical explorations of a team of doctors who are intent on cutting parts of him away, to see if it helps, in a ward where no-one gets out alive. In that sense it felt like watching an episode of Reginald Perrin, engendering a very 1970s sensibility. The very gentle surrealism of it all sings out to me. Organs and health issues are given amusing if appropriate names (the diapason is both a tuning fork and the just octave in Pythagorean tuning), likewise medicaments (2-Nup etc.). Kleinzeit talks of the cold, soft-padding paws under the ground in the underground that step from below exactly where you place your own feet as though you walked on the soles of some subterranean beast. Underground (capital U as it's a proper noun), Hospital, Word, Death, God (and Vishnu) all interact as characters in their own right, and in his descriptive passages, even the scenes of action, the lens through which the reader sees is of a peculiarly, and wonderfully, Hobanian design. Let me quote a few lines from the very first page:

He put his face in front of the mirror.

I exist, said the mirror.

What about me? said Kleinzeit

Not my problem, said the mirror.

... He left the mirror empty and went to his job, staying behind his face through the corridors of the Underground and into a train.For readers who love playful use of the English language, playful and profound, then Hoban is a delight. It's no wonder that a wordsmith of the calibre of Will Self can say that Hoban is his hero. Right the way through, Hoban toys with the quotidian interactions of commuters, paper-shufflers, seekers of fame and fortune, and the lonely, connecting through sparring handwritten comments on the posters and walls of the subway. His characters look for freedom but like timid mice daren't approach it when they find it. And smeared over the top, like a simple but tasty strawberry preserve, is a very healthy dose of smut. In fact, such smut that I became irrationally concerned that my son never discovers his backlist of children's novels.

Fair to say I was immediately entranced by this book. It does many things brilliantly, lots of things wonderfully, and slips along like a swollen river of words, so fast indeed that I worried I wasn't giving it enough attention and so had to deliberately slow myself down, attempting to rein-in galloping paragraphs and to savour each line. One such is this last offering with which I leave you, delivered by Sister to God in a dialogue about the inherent illness of mankind:

It isn't a matter of finding a well man, it's a matter of finding one who makes the right use of his sickness.

Comments

Post a Comment